This is the fourth in a series of blog posts about the Sustainability Frontiers conference, written by Laila Mendy. The first can be read here, the second post can be read here, and click here for the third.

Diego Galafassi curated the next session and explained how this session appeared to be cross-cutting, noting how the idea of the imagination and imaginaries had been brought up throughout conversations in the conference. Galafassi introduced the topic, shortly explaining that imagination and creativity is a real component and important skill for transformation. He was joined by panellists Myanna Lahsen, Henrik Karlsson and Lara Houston.

Myanna Lahsen began, following the same structure as the earlier sessions, with a five minute intervention into the theme from her own field. She probed the idea of the individual when it comes to inner transformations, suggesting that this is an important component but also a significant hurdle in societal change. As a cultural anthropologist by training, Lahsen explained that looking at who counts and where impact happens in democracies gives an indication that it is the economic elites, business-oriented organisations and interest groups who matter. So when it comes to the idea of inner transformation, scaling that is critical.

What may seem inner and private, she suggested however, is deeply social and political. This is where Sustainability science is struggling to work. There is a tendency to put faith into groups of people and assume that people will mobilise around an issue; scaling happens through the numbers. Social activism is assumed to be progressive, but we know this is not always the case. Little attention has given to how people come to know what they know in the first place. Lahsen argued that the political economy and market place of ideas is neglected in this field.

Lahsen then explained this issue in the context of mass media communications. Cognitive sciences show that repetition is needed to shape people and give them the ability to collectively frame an issue. This, arguably, is not understood as a power agent. Yet much of media is owned by the same groups who legitimise certain political issues through their own agendas. The example of Brasil was given, where the media was not recognised in terms of power. Addressing this gap is critical for social action: social marketing can lead to change, she said, without leaving the movements pushing an issue without support.

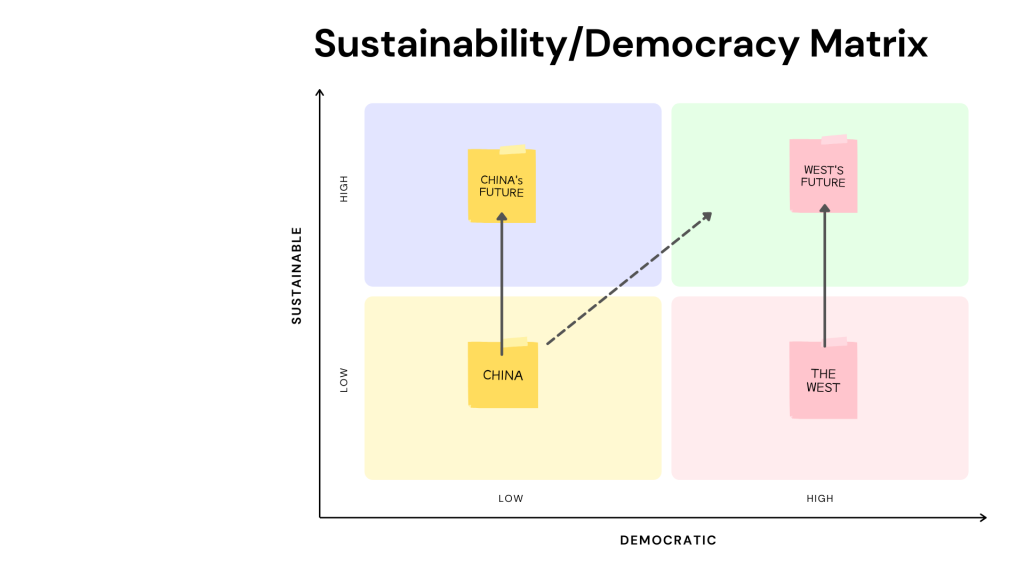

Henrik Karlsson followed with a presentation on the diversity in futures in literature and fiction. He started by plotting a matrix with general images of a desired future, prompted by his reaction to a Chinese participant in a Thai workshop who said sustainability is only possible with a strong leader. This table is imitated below:

The dotted arrow indicates “wishful thinking” from the West on the behalf of China’s future.

The figure above demonstrated how there is an assumption about what other (groups of) people might find desirable when discussing sustainable futures. He had assumed that China would move to the upper right quadrant. This began a search for the different forms of futures and what could be understood as desirable. Was it to maximise happiness? Human utility? Or perhaps it was about minimising suffering.

Asking different groups of environmental philosophers will get you different ideas on what means can be justified for the ends of sustainability futures, he explained. He quoted a Finnish philosopher, Pentti Linkola, whom Karlsson described as an eco-fascist for making the statement that “We still have a chance to be cruel. But if we are not cruel today all is lost.”

It was not only literature that had such provocative ideas of the future. Karlsson offered an image from a recent exhibition which probed the questions about whether the future needed us. The idea of human extinction, though, is not necessarily something he wants people to aim for when opening up ideas about alternative futures. Rather this was mentioned merely to provoke new ways of thinking about what wider possibilities could exist.

The final presentation came from Lara Houston who discussed creative practises for futures transformations. This included different forms of aesthetic, experiential, multi-sensory and embodied experiences to enable transformations to sustainability.

One exemplification of this, The Hollogram, was elaborated on in the presentation during which it was described as having enabled a collective imagining of sustainability transformations through expanding shared meanings and feelings. The experience demonstrated how knowledge politics can be misunderstood in sustainability sciences. The idea of empathy was brought up here in how it can be motivating for mobilising action towards sustainability during processes of change.

The impact was a transformation on the understanding of relationships, particularly of friendship. The experience had challenged cultures of financialisation, in which some forms of friendship can be considered transactional. The move away from these modes of relationships may, it was argued, lead towards a shift in more sustainable living.

In the plenary, Galafassi asked the panellists to think more on imaginations as a type of transformative capacity. Houston responded first by discussing imaginaries in the context of art installations. Imagination points towards an individual cognitive experience, but this is done within a shared collective. Lahsen had similar approaches, this time considered in terms of agency and obstacles in new technologies and media systems. There are ways to overcome obstacles to opening up ideas and capacities, such as public wisdom councils. Social marketing really works, but there is aversion to this. Polarisation is happening, but these technologies can be used for good: VR empathy, for example. See the Oxford Handbook of Compassion Science for more examples. For Karlsson much of this discussion concerned interdisciplinary partnerships. He suggested that throughout history, academia has had better practises for moving across disciplines. These should be explored again today.