On 9 October professor Stacy VanDeveer held his inauguration lecture after being appointed as the 2023-24 Zennström visiting professor. Stacy VanDeveer is a professor and chair of the Department of Conflict Resolution, Human Security & Global Governance at the McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies at University of Massachusetts Boston.

Returning to his research roots

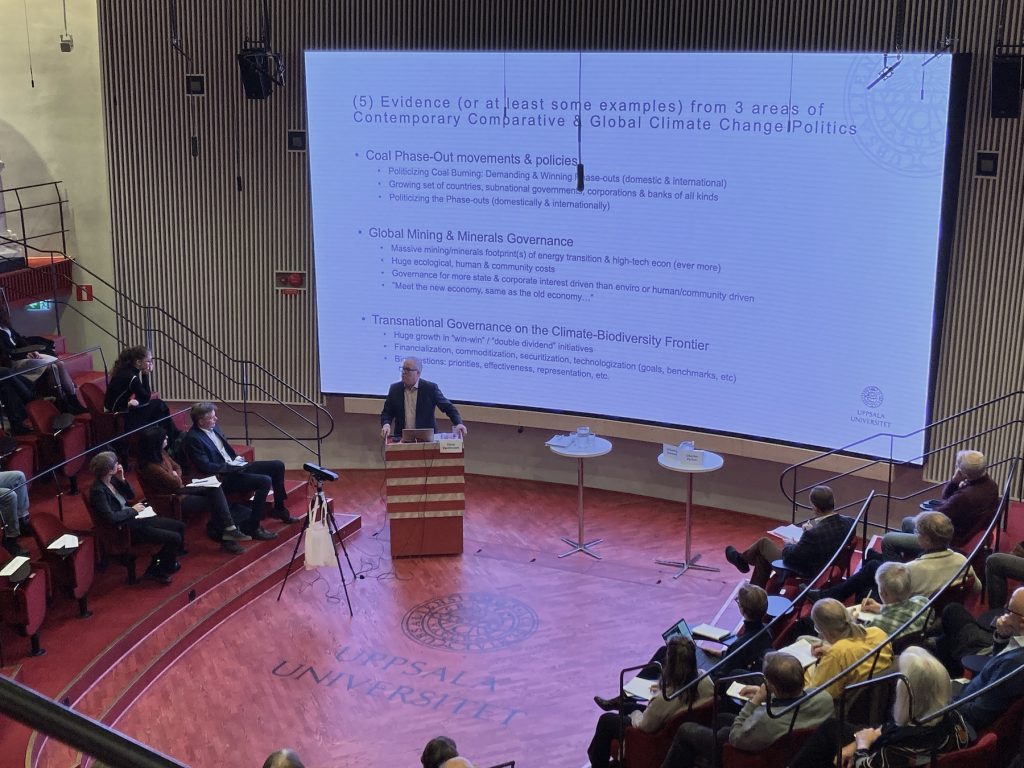

In front of more than hundred participants at Humanistiska teatern, among which were his husband and his mother, VanDeveer gave an overview of his research which has been devoted to questions of global environmental politics and the interfaces between science and policy. He has explored the roles of experts and power relationships in policymaking, US and EU environmental and energy politics, and processes and institutions of global environmental policymaking. The theme of his PhD dissertation was on the regional collaboration around the Baltic and Mediterranean Sea. With his appointment as 2023-24 Zennström visiting professor at Uppsala University, he has returned to Scandinavia, which was part of his initial research areas.

Why has better scientific knowledge not advanced climate policy more?

Even though the collaboration around the Baltic and Mediterranean Sea involved the affected governments, they were also driven by scientists in different capacities. A question he explored was whether scientific participation had any impact on policymaking. He found that the countries that had institutional capacity had the best opportunities to transform scientific, technical and environmental knowledge into policy action. Later he studied co-production processes of knowledge between scientists and policymakers.

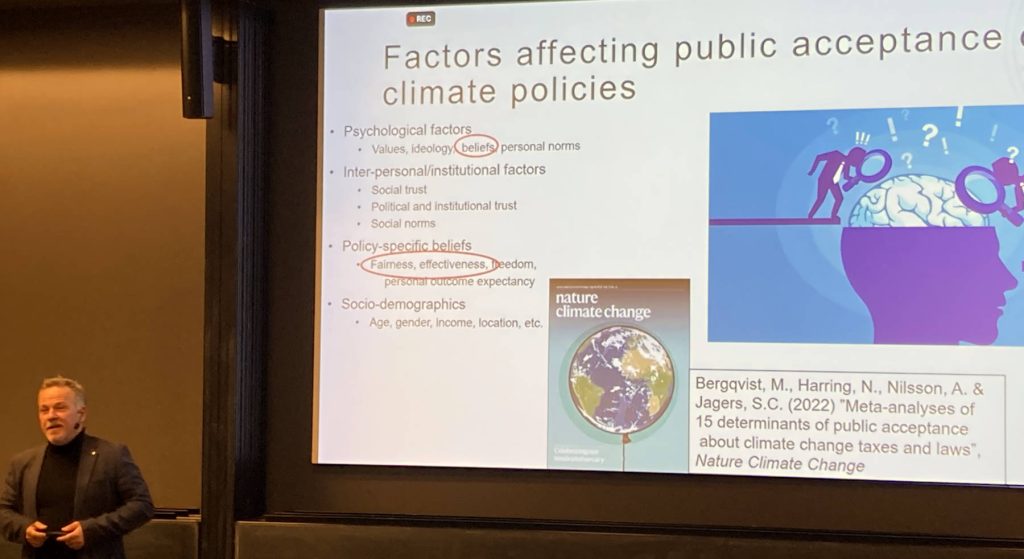

On the role of experts, VanDeveer concluded that scientists have often not made themselves particularly useful in environmental policymaking. At the same time, there has been a notion that growing scientific consensus, together with more certainty and confidence, increasing awareness and knowledge among the public and policymakers, and visibility of the impacts of climate change, should translate into political action. However, this has not happened. The consequence is that we still have mediocre climate polices, which are now even rolled back in some countries, including Sweden.

Discursive power and climate change consequences empower climate leadership

So what makes for efficient climate leadership if not scientific facts and expert knowledge? One approach has been discursive power using a combination of scientific language and justification in social and economic arguments. While movements understood it was difficult to influence central governments, they begun to venue shop, identifying institutions or organisations willing to move ahead and lead by example. Knowledge has been institutionalized within institutions and companies, by employment of environmental experts. There have been attempts made to drive normative change overtime. The European Union is a leading example by having set high product standards that have had an impact on manufacturing norms even beyond Europe.

Another fact that promotes climate leadership is that climate issues are no longer a remote problem for those of us in the Global North. Consequences of climate change and are beginning to affect people’s lives at our door step. Furthermore, climate issues are increasingly linked up with other political issues and grievances.

Opponents of climate transition cause climate policy backlash

At the same time, opponents of climate transition have also learned from the success and failure of climate leadership and grievances, and understood how they can shape efficient counteractive measures. One way is to re-politicise the norms, arguing that environmental policies were not enacted for a good cause. They have chosen not to challenge policies in full and at a central level, but to turn down selected parts of such policies. Opponents have made attempts to delay policies, by claiming that they are not against climate policies, but that changes are happening too fast. The groups fighting back are powerful with both economic and media resources. In recent years, environmental policy backlashes have also occurred in many countries, such as Sweden and the United Kingdom. Even though citizens usually do not support attempts to roll back adopted climate polices, climate issues are generally not prioritized by the electorate. Immediate issues, such as crime, are often more concerning, and these types of grievances have been successfully exploited. With such examples, VanDeveer concluded that there will be no “magical moment” when the need for climate policy action will be broadly accepted and supported. The climate transition will accordingly be a constant struggle ridden by conflicts.

Panel discussion on the progress of climate politics and the role of (political) science

The lecture of Stacy VanDeveer was followed by a panel discussion led by Mikael Karlsson, Senior Lecturer in Climate Change Leadership lecture. Participating in the panel was Naghmeh Nasiritousi, associate professor in political science, Johanna Sandahl, chairperson of the EEB (The European Environmental Bureau) and Charles Parker, professor in political science.

The panelists were invited to reflect and comment on the presentation. While agreeing with the statement that no magic moment will occur for the acceptance of climate policy, Parker stressed that we should also look at the cumulative effect of science. Increasing scientific evidence has paved the way for today’s international cooperation around climate change, whereas a transformation of policy is still needed for the solutions to come into play. With new and more radical movements growing stronger, the traditional environmental NGO sector is struggling to deal with the question of climate change. Sandahl advocated for co-production of knowledge, and not just looking at environmental science but also bringing in perspectives from political science and humanities. Zooming out, Nasiritousi compared the backlash of climate policy to a more general backlash of democracy. She pointed to a bias in the literature towards successful cases. Instead, we need to study the conflictual politics of climate change.

Urgency, solidarity and leading by example can drive change

Despite the growing body of knowledge on climate change and its solutions, there is a notion that progress is still slow. Parker made a point that the time scales of climate change and international relations do not match. Even though the conversation around climate change started 50 years ago, we did not get any proper international agreement before 2015. Yet, from a diplomatic perspective, this is rapid. The problem is that the system is blinking red, and we need to act now. A lack of solidarity in politics was pointed out by Sandahl as another explanatory factor, which she saw as counterproductive given that climate change is increasingly affecting people’s lives. Nasiritousi painted a global picture of climate politics as complex and polycentric, and she stressed the need for courageous countries to take the lead in climate leadership. The discussion briefly touched upon the role of (political) scientists and the impact and the expectations for the upcoming COP28.

Research interest in the effects of activism

During the open discussion, a broad range of questions were raised. The topic of adaptation was brought to the conversation, where a lack of climate leadership has been seen. VanDeveer argued that compared to mitigation, we have not been able to find ways to make money of adaption, which is hampering its implementation. One of the final questions that sparked interest across the entire panel was on activism. The panelists agreed that more research on the topic is needed, both in terms of understanding different arenas of activism but also to understand whether disruptive activism is helping or hurting climate policy.

After the presentation followed a mingle. Seasonal finger food was served, showcasing Scandinavian fall produce such as pumpkin and beetroot. Most of the audience stayed and continued the conversation with both panelists and the new Zennström professor, Stacy VanDeveer.